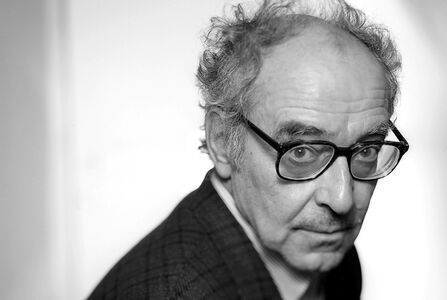

Jean-Luc Godard is an Icon like Che Guevera. You might not have seen his films but would like him to be a part of your lexicon. You might not be able to pronounce his name correctly but he like Che, is a part of your life.

I could pronounce his name having French as a subject of my studies in St. Xavier’s College and Father Roberge being your teacher of film studies you quite couldn’t miss it. And he did enter my lexicon early, thanks to Father Gaston Roberge, The French Canadian Teacher.

To be honest, the first several viewing of Godard’s Film went just over my head. In our class we had film screening and Father Roberge would analyze and explain it to us. For Godard he did not. He wanted us to see the film over and over again. And so I did.

I looked at the film and saw moments. Famous moments. Moments in Breathless when Belmondo looks at an image of Humphrey Bogart, fingers his lip and says “Bogie,” almost as if he were saying the word “God.” Yet Godard’s films, even as they gazed back at the past, also stared into the future. Godard wanted to use cinema to take the entire modern world, the look and feel of life in the sterile comfort zone of the 20th century, the products and pop images that saturated our existence, the myths and systems: political, cultural, economic, romantic, we all lived inside, whether we knew it or not and somehow drag it all onscreen.

In Don Bosco School , our English teacher William Rozario, had taught us that an essay has an Introduction, a body and a conclusion and for long I carried this to the Film Study Classes. It worked all right for most of the films but not for Goddard. Father Roberge in his class had commented on the narrative structure of a story. But Godard was beyond. The archetypal tripartite story structure is outlined in Aristotle’s Poetics. Here is a 1746 version of Aristotle’s words translated into English: The beginning supposes nothing wanting before itself; and requires something after it: the middle supposes something that went before, and requires something to follow after: the end requires nothing after itself, but supposes something that goes before. Godard did in films something akin to the way James Joyce entered the human mind and put them right onto the page. Godard’s characters lived the life that they were living, and also talked, onscreen, about what that life meant, and even talked about the fact that they were talking about it. They talked about books, cinema, work, love, and language. Godard was turning cinema into a three-dimensional vision of experience that was always aware of itself.

Much latter I came across his famous quote: A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order. His films to me is like a dream where you see sequences but not in a linear format. No one is certain about dreams. If they tell you they are, they're either fooling you or themselves. There isn't a universally accepted definition of dreams. The whole idea behind them isn't wholly understood. And most of us don't understand, or heck, even remember, our own dreams. Authentic and Illusory. Authentic dreams are those that reflect actual memories and experiences of the dreamer. Illusory dreams, on the other hand, contain impossible, incongruent, or bizarre content. Dali-esque stuff. That quality made Godard’s cinema revolutionary and exciting, and also challenging and forbidding. To watch a Godard film was to enter a playful labyrinth dream, with the viewer at the centre.

Godard was also the grand deconstructionist of cinema, obsessed with reminding the audience for a movie that they were watching a movie. Deconstruction as in the philosophy of Jacques Derrida. Jacques Derrida was a French philosopher, born in French Algeria. Derrida is best known for developing a form of semiotic analysis known as deconstruction. Deconstruction is a philosophical movement that questions traditional assumptions about certainty, identity, and truth. Deconstruction denies the possibility of a pure presence and thus of essential or intrinsic and stable meaning — and thus a relinquishment of the notions of absolute truth, unmediated access to "reality" and consequently of conceptual hierarchy. And that made him, at times, a bit like the James Joyce who people always say they studied in college because there’s almost no way to read him if you aren’t studying him in college. “Breathless” was a hit, and it hit an art-film slot, bridging not just Old Hollywood and the new wave but the audience that wanted to look at a movie screen to forget itself and the audience that projected itself onto everything it saw.

Every piece of Art has a Form and a Content. In Godard’s film specific application of deconstruction has been less obvious than the breaking of the form. Without deconstruction in Godard’s film we would be left with bland narrative, approached from the bland perspective that they're basically the same, but with a few twists here and there. Godard’s film should be approached from a deconstructive point of view, but what's most important is to realise that deconstruction challenges the very fibbers of interpretation itself, pointing out contextual and institutional barriers that often accompany film in general. Godard became an artist who was not interested in the pretence of telling stories, or in creating characters who weren’t conduits for his larger perceptions.

Godard, virtually the inventor of modern movies, is the rare filmmaker who can be called a god of cinema. The first Godard movie I ever saw was Breathless at Alliance Francaise, a special screening which Father Roberge had arranged. It became the standard thing to say about Godard that his movies from “Breathless” to “Weekend” added up to one of the greatest runs in cinema history, but then he had his Marxist break with everything (a schism that the impish 2017 biopic “Godard Mon Amour” amusingly posits as a narcissistic personality crisis of elitism run amok, at which point it became acceptable for even high-end film buffs to say that his work had become impenetrable. Then he had his comeback in 1980, with the rapturously received “Every Man for Himself.” But that was an anomaly. Going forward, Godard’s films retreated very much into a cerebral asceticism, typified by the 1994 video work “JLG/JLG.” That said, the last film of his I saw, “The Image Book” (2018), is like a postmodern dread of our time.

I think it’s in the nature of who Godard was that he became a meta deconstructionist of the soul, someone with a laser mind that could slice through anything, including how the powers that be had conspired to turn life itself into an opiate of the masses. And so he came to see the pleasures of movies; the story, the romance, the escape, as an opiate of the masses. He was probably right. His own refusal of escape made him daunting to the end, and that’s part of Godard’s legacy. Yet before he became that visionary scold, Jean-Luc Godard was someone who saw the very act of making cinema as a salvation. That’s what you feel watching his greatest movies: that they’re as alive as the world around them. And that cinema should never be anything less.