Bengalis are parochial by nature. They are either Ghoti, residents of West Bengal or Bangal refugees coming from erstwhile East Bengal. Bangals like Ilish (Hilsa) and Ghotis like Chingri (Prawn). Bangals support East Bengal, Ghotis support Mohan Bagan.

In cinema there used to be a clear divide. Uttam Kumar or Soumitra Chatterjee.Satyajit Ray or Mrinal Sen.

The dividing line has thinned in the coming generation as they have not been brought up within this parochial divide. To the earlier generation Satyajit Ray seemed content to portray Bengal from the artist’s viewpoint—painting beautiful canvases devoid of any real analysis of India’s condition. To them Ray has ignored the problems that are predominant in Indian society—economic exploitation and political repression.

Wheras, Mrinal Sen was a cult hero. In his films he has transformed a very commonplace film style into a socially relevant, politically committed cinema. To them the Bengali cinema had been quite removed from social realism and relevance. It is Mrinal Sen who began discussing these problems in a non-romantic manner, in a manner that is made Indian audiences sit up and take notice. He has faced obstacles: difficult producers, reluctant distributors, and, of course, a disapproving Censor Board. But he managed to bypass them and is the only Indian director who discussed contemporary political situations.

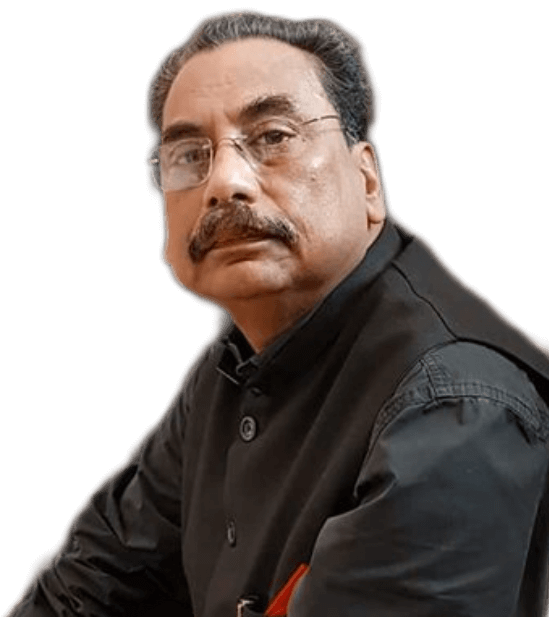

Satyajit Ray was born in the city of Calcutta into a Bengali family prominent in the world of arts and literature. Satyajit Ray's ancestry can be traced back for at least ten generations. Ray's grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury was a writer, illustrator, philosopher, publisher, amateur astronomer and a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious and social movement in nineteenth century Bengal. He also set up a printing press by the name of U. Ray and Sons, which formed a crucial backdrop to Satyajit's life. Sukumar Ray, Upendrakishore's son and father of Satyajit, was a pioneering Bengali writer of nonsense rhyme and children's literature, an illustrator and a critic. Ray was born to Sukumar and Suprabha Ray in Calcutta. Starting his career as a commercial artist, Ray was drawn into independent filmmaking after meeting French filmmaker Jean Renoir and viewing Vittorio De Sica's Italian neorealist 1948 film Bicycle Thieves during a visit to London.

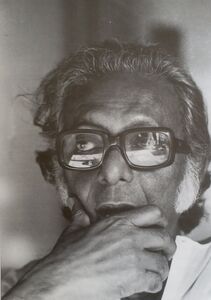

Sen was born in the town of Faridpur, now in Bangladesh in a Hindu family. After finishing high school there, he left home to come to Calcutta as a student. He studied physics at the well-known Scottish Church College, and subsequently earned a postgraduate degree at the University of Calcutta. As a student, he got involved with the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India. Although he never became a member of the party, his association with the socialist Indian People's Theatre Association brought him close to a number of like-minded culturally associated people. Sen's interest in films started after he stumbled upon a book on film aesthetics. However, his interest remained mostly intellectual, and he was forced to take up the job of a medical representative, which took him away from Calcutta. This did not last very long, and he came back to the city and eventually took a job as an audio technician in a Calcutta film studio, which launched his film career.

Satyajit Ray and Mrinal were in fact friends and were ardent admirers of each others work. Praise from both sides can be found in print on a number of occasions.

But their style differed. Greatly. In my Mass Communication Class in St. Xavier’s College conducted by Father Roberge, Mrinal Sen summed up his style when he emphasised: “Remember, when you touch your multifaceted medium, you touch man. As you serve your medium, you serve your conscience too. And as you walk into the world, you take chances or play safe. By taking chances, you achieve or perish. Or, playing safe, you just survive. The choice is yours..."

Sen too had countless votaries for his films imaging social reality. The contemporaries, all from educated and established families, and bound by their passion for cinema if not ideology, shared a rivalry. Sen, to quote Derek Malcolm, "traced the social and political ferment of India with greater audacity than any other Indian director." He showed unrest, Naxalite or otherwise, in his city and throughout India. He mirrored class conflict as much as middle-class angst. He sang of tribal exploitation and global collapse of the Communist dream. Yet, Sen established that an iconoclast needs to demolish only the illogical, not every value that's prevalent.

Perhaps his birth in Faridpur - now in Bangladesh - and residence in Kolkata determined the content of his films. There's no doubt that Sen was breaking traditions to create conventions. The non-narrative structure is an example, the open ending is another. It turned the audience into a participant free to bring the plot to a conclusion of his choice. Sen was directly inviting the viewer into the lives of his characters. With him behind the camera, cinema changed tenor, format, and language.

All of this won Sen laurels and awards, at home and abroad. It earned him brickbats too. Was he wearing his ideology on the sleeves of his ever-white kurta? Was he indulging in technical gimmickry? Was he imitating French Nouvelle Vague? Was he concocting a cocktail of Existentialism, Surrealism, German Expressionism, and Italian Neo-realism? Was Brecht his fig leaf - or was he taking a leaf out of Latin American art?

Sen was always ahead of his peers in experimenting with form. His freezes in Akash Kusum as a transition devise were unique for its time. His Baishe Shravan was so poetic, so lyrical! Although identified as Marxist - who is generally rational and rigid – Mrinal Sen was more concerned with his characters and then came the ideology.

Bhuvan Shome that flagged off the New Wave in India is a watershed in its use of outdoor location, Utpal Dutt's signature performance, and substitution of traditional story telling with a new vision. It had all the characteristics of a New Wave cinema. Mrinal Sen’s form was never static. He didn't follow conventions; he took risks and created his own, making restlessness his form. Mrinal Sen had a specific viewpoint but at his best he transcended it to embrace universalism and humanism.

Ray chiselled and perfected his films; Sen caught reality as it was - raw. Ray was a sculptor Sen was our own artisan from Kumartuli who created our mother Durga whom we worshiped. That candid, cinema verite in fiction style has not been equalled in Indian cinema, nor has Sen been given the recognition due for this.

Yet today, when one examines Indian cinema, especially contemporary movies made with an independent spirit, many feel that he is stylistically one of the major influences for those who are poised to change the language of visual narratives.

If Srijit Mukherjee shared Sen's title of Baishe Srabon for his movie, Mainak Bhaumik is more direct about expressing his stylistic parallels. "One can call it a steal or homage. He is the one who made me want to become a filmmaker. From Bhuvan Shome to Interview, from Ek Din Pratidin to Akaler Sandhaney - there is so much he has done that we directors are trying to incorporate in our cinema. Today what is being described as new-age facebook generation of Indian filmmaking is directly inspired by his work.

Mrinal Sen is a visionary. Being far-sighted, whatever he did decades ago were much ahead of the times. People might not have understood his work when they did it but today, the world is discovering him. Sometimes when today's directors try out techniques that Sen used some 40 years ago, there are people who say wow and also attribute these stylistic devices as discoveries of these filmmakers. I'd be glad if these directors who are influenced by Mrinal Sen acknowledged their inspiration in public.

In every art there is a form and content. Mrinal Sen’s form and content is influenced by his life style. It is Sen's way of leading his life that has been an influence on his work. The way he looked at stories, told them and chose the characters brought a different sensitivity to cinema.

To my mind Mrinal Sen was Deconstructing. Deconstruction as in the philosophy of Jacques Derrida. Jacques Derrida was a French philosopher, born in French Algeria. Derrida is best known for developing a form of semiotic analysis known as deconstruction. Deconstruction is a philosophical movement that questions traditional assumptions about certainty, identity, and truth. Deconstruction denies the possibility of a pure presence and thus of essential or intrinsic and stable meaning — and thus a relinquishment of the notions of absolute truth, unmediated access to "reality" and consequently of conceptual hierarchy.

The specific application of deconstruction has been less obvious than the breaking of the form. But it slowly crept into the pours of the films of Mrinal Sen, in a calm and respectable fashion. It has been an indirect seeping into the crevices of his content, but it has seeped nonetheless. Most notably, the immediate thoughts in relation to deconstruction are that it has been an effective tool in breaking up and separating the narrative. It has been demonstrative in showing that there is indeed a keen divide between the linear narrative and nonlinear story telling. When talking to Mrinal Sen you realize this more as he jumps from one subject to the other but there is a binding in the overall format.

Without deconstruction in Sen’s film we would be left with bland narrative, approached from the bland perspective that they're basically the same, but with a few twists here and there. I suggest that the films of Sen should be approached from a deconstructive point of view, but what's most important is to realise that deconstruction challenges the very fibbers of interpretation itself, pointing out contextual and institutional barriers that often accompany film in general.

Cinematography relates directly to the written word. Whereas for Sen it illustrates a relationship to a thought. Now this doesn't mean it is not written by word, more that it has to be credited in the same way we would like at writing. Like the written words we can see on a page, the meaning is often obscured and split into multiple directions, rather than maintaining a strictly linear attitude. Much in the same vein, the image, i.e. what you are seeing on the screen, cannot be limited to one single meaning. In fact it is impossible to constrain the image to a single set of meanings, hence deconstruction theory.

The arguments go so far as to say that in essence meanings that are constructed will naturally be contradictory. Neither can a director's intent be said to create a solid meaning, because by the nature of humanity, intention will never be a unity, only divided. In fact, film itself is flawed by the same application of logic, because it contains both a visual and audio difference. By being of these two sections, film itself is maintained of two different communications medium and as such, the wholeness and togetherness of a film is unintentionally artificial. Thus the image cannot be of a single track meaning, because, like the previous sentences describe, it becomes obvious that as film is split between image and audio, it is incoherent.

Deconstruction in Mrinal Sen’s film is an issue of philosophy. To conclude the consequences of a deconstructive perspective do concern interpretation. Deconstruction does for Sen’s film what an abstract painting could do. Is that a negative, or a positive?

Instead, is deconstruction just a way to show the shackled constraints around permissions and restrictions of decisions, based on meaning? Deconstruction at it's heart, at it's essence, is in essence doubled natured; it wanting to stretch and expand the boundaries of logic, but also, strictly speaking, wanting to remain distinctly logical.