Nelson Mandela was to visit Calcutta. I was then working in Anandabazar Patrika and we went berserk. A huge Special Feature was planned something to the tune of 24 additional pages. Believe me in those times this was elephantine. But sad to note that though he died on 5th December and the news was broken at around 12.30pm, the same Anandabazar Patrika or its sister publication The Telegraph failed to carry the news and the obituary in the morning paper.

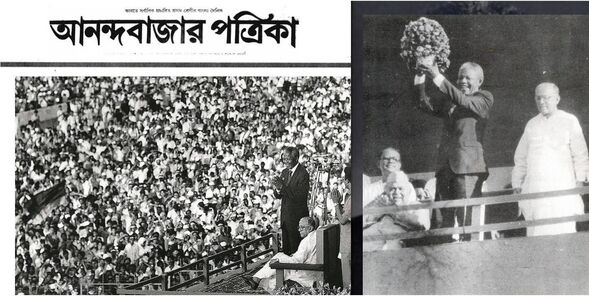

On a crisp winter morning armed with several copies of the day’s edition I made myself to Eden Gardens. No, no not to watch the cricket match, but to join the felicitation of Nelson Madlela at the Edens where it was organised. The VIP card was of no use. It gave me entry but did not ensure a seat. There were swarms of people. We were like locusts landing on the fresh paddy field about to be harvested.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, fresh out of 27 years in jail, was in Calcutta, in the winter of 1990, to be exact October 18th,on his first-ever visit to the country that had supported his struggle with passion. The Eden Garden cricket stadium was packed to far more than capacity, the green completely covered, the stands overflowing.

He looked to his left, he looked to his right. His head had never turned to see, nor his eyes ever captured, such an expanse of humanity at one go as he now saw.

To say South Africa’s man of destiny was stirred would be to say the obvious. He was stirred beyond his expectation, his experience. To his host, West Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu, seeing such a large gathering was nothing new. But even for the veteran Communist leader, there was something exceptional about that day. Jyotibabu had not seen such wild enthusiasm exploding in a public meeting, at least not since the time Calcutta greeted the then “just released” Bangabandhu, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Neither host nor guest forgot the experience, nor the real meaning that lay behind it,the turning of one of history’s most stubborn pages.

Here was a leader of leaders whose charisma and influence, strength and impact, had grown with each year that the apartheid regime had him jailed, and who had become a symbol not just for South Africa’s human rights struggle but for human rights across the world. Here was a man whose perseverance had led him to be released by a sobered regime that was, at last, seeing all its delusions collapse. Here was a man who stood tall at the end of a struggle and at the start of its consequence: responsibility.

A major apartheid thesis, apart from its lies, was “the Bantu can agitate, the Bantu cannot govern”. The use of that racist term was in itself misapplied in the case of South Africa’s varied population. But it was the propaganda in it that did the greatest damage. It was meant to, and did, demoralise a people who knew time was on their side but were mystified by the working of the clock’s innards.

Mandela, on this, his first visit, was asked by people he met, and not just the inquisitive media, how he planned to vestibule struggle into power, agitation into governance. The query came from concern, not cynicism. Mandela did not give elaborate answers but his demeanour showed he was in some tension. And in Calcutta, meeting the progeny of struggle, the local Marxists, in power, was an opportunity for him to learn something. The CPI(M) was at the head of a Left coalition. That, for Mandela, was a crucial fact—coalition. “Commies can agitate, they cannot run an administration”, was a remark that had been heard in the early and mid-1970s until the Left Front showed it could do so and—until the milk curdled in the 2010s—with flair.

And so, for Calcutta, there was more to Mandela than an icon. There was in him an ‘amader moto’ quality...a ‘like us-ness’. It was seeing a man whom the South African Communist Party, known the world over as the SACP, had accepted as ‘amader moto’ and more, had tur¬ned to for what can be called a leadership-on-loan. Mandela was not a Communist, but the SACP knew of no one more sensitive to the class struggle than him, no one more committed to an egalitarian order. The SACP had an ideology, its cadres had commitment. But what of a leadership that captured the South African political imagination? That the SACP did not have, whereas the ANC had not a few mass leaders, the greatest of them being NRM, hailed by the world as Mandela and by his very own, as ‘Madiba’, a teacher who had the depth of a deep aquifer.

The Triple Alliance between the African National Congress, the Confederation of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the SACP was to embody a working alliance between a national movement and the Communists such as had not been seen anywhere. “I am told the Communists are using us,” Mandela was to say famously. “Maybe they are but then are we not using them as well?”

‘Using’ is a pejorative expression. Mandela knew that but he was not going to waste time being politically correct when he needed to be politically frank, politically wise, politically courageous. Joe Slovo, leader of the SACP, than whom there could not have been a more orthodox Communist, saw the need for mutual ‘usage’.

Mandela showed what he alone among world leaders had the moral authority to show, which was, the ability to take each issue on merits, each contention at its face value, and call a spade a spade. Did this mean that he made no mistakes? No, far from it. His trust was misplaced when, for instance, it came to Gaddafi and Mugabe. Not every spade-looking shovel is a spade.

In an age when idealism and pragmatism look north and south, ethics and political decision-making are at cross-purposes, the ‘good’ is regarded as naive, Nelson Mandela showed a different example. His goodness was not simple-minded, nor his idealism made of rose-water. He knew it was smart to be good, good to be smart. He had said, during the struggle, that his non-violence was tactical, not philosophical. Be that as it may, it was effective. Nelson Mandela was by training both a lawyer and a boxer. He knew when to advance, when to retreat, when to step aside. He also knew the value of surprising his opponent. But above all, he knew that combat has codes, just as protocol does. His personal and political conduct was, if anything, supremely brave and supremely ethical, both values coming from his mind, not his heart.

Let us not fix a halo over Mandela’s head. To make a saint of a supremely cerebral man does no credit either to sagacity or cleverness. Let us see in him, rather, the possibility of moral successes through intelligent act¬ion and the breakthroughs for intelligence in ethical choices.

After the felicitation there was a small gathering for Mandela to meet a selective list of guests. I inched myself to the club room at Edens to hand him the copies of the special issue of Anandabazar Patrika and The Telegraph. Needless to say he was much impressed and his daughter Makaziwe Mandela asked for more copies. I handed several more, than as an afterthought asked a copy back. She was surprised but returned a copy . I told her I want it autographed. I took it to Mandela and with a flourish he gave a one big autograph across the paper. I returned to office triumphant like an eagle on the days proceeding. I showed the signed copy to all when a junior artist who had helped to do many of the artwork came up to request me for the same. I did not have the heart to refuse. Not after you meet such a lion hearted gent. Without even a moment of hesitation I gave the copy away.

Mandela died of a lung infection on 5 December 2013 at his home in Houghton, Johannesburg. He was 95 years of age and surrounded by his family. His death was announced by President Jacob Zuma. His funeral is expected to take place after 12 days at the Union Buildings before burial at his native village Qunu.

— with Jagori Bandyopadhyay.